With thousands of archaeological sites, Jerusalem is one of the most excavated cities on the planet and to walk its streets is to walk through thousand years of history. This ancient city has been fought over more than any other place. It has been conquered, destroyed and rebuilt many times and Hadrian played a significant role in Jerusalem’s physical development.

In AD 130, on his grand tour of the eastern part of the Roman Empire, Hadrian visited the devastated city of Jerusalem , accompanied by his young lover Antinous. He established a new city on the site of the old one which was left in ruins after the First Roman-Jewish War of 66–73.

The new city was to be named Colonia Aelia Capitolina.

Aelia is derived from the emperor’s family name (Aelius, from the gens Aelia), and Capitolina refers to the cult of the Capitoline Triad (Jupiter, Juno and Minerva).

![Drawing of the reverse of a coin from Colonia Aelia Capitoliana, depicting Hadrian as founder of the colony]()

Drawing of the reverse of a coin from Colonia Aelia Capitolina.

The reverse depicts Hadrian as founder ploughing with bull and cow the sulcus primigenius (aboriginal furrow) that established the colony’s pomerium (sacred boundary). The vexillum, or military standard, in the background represents the veteran status of the colony’s new inhabitants. The legend, COL[ONIA] AEL[IA] KAPIT[OLINA] COND[ITA], translates “The founding of Colonia Aelia Capitolina”.

Exactly when the construction of Colonia Aelia Capitolina began is still a matter of debate. Some scholars, relying on the writings of Cassius Dio, contend that the name change and the beginning of the construction of Aelia Capitolina occurred in connection with Hadrian’s visit in 130, perhaps even setting off the Second Jewish Revolt. Others, relying on the writings of the 4th century church father

Eusebius, propose that the change of name occurred only after the Second Jewish Revolt was suppressed in 135. However, finds from recent excavations of the Eastern Cardo suggest that not only the foundation of the Roman city predated the Second Jewish Revolt but that the establishment of the city preceded the uprising by about a decade.

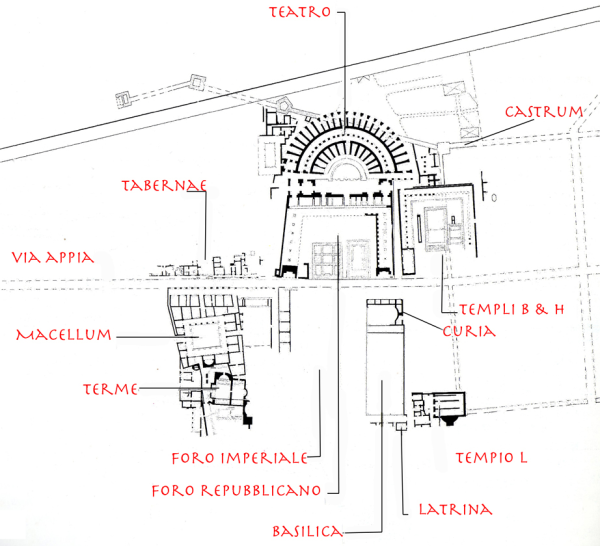

The urban layout of Aelia Capitolina was that of a typical Roman town; an orthogonal plan with a square grid of streets set at right angles. It was a military colony, a traditional and official settlement of veterans of the Tenth Fretensis Legion which had been in Jerusalem since the First Jewish Revolt and probably other Roman troops.

The colony was established just north of the camp of the 10th Legion. Its major buildings were the Porta Neapolitana in the north (now the Damascus Gate), a Temple of Aphrodite, two forums and, according to Roman historian Cassio Dio, a Temple of Jupiter built on the site of the former Jewish temple, the Temple Mount.

” At Jerusalem Hadrian founded a city in place of the one which had been razed to the ground, naming it Aelia Capitolina, and on the site of the temple of the god he raised a new temple to Jupiter. This brought on a war of no slight importance nor of brief duration, for the Jews deemed it intolerable that foreign races should be settled in their city and foreign religious rites planted there.”

– Cassius Dio, Roman History, 69.12.

![Reconstruction drawing of Aelia Capitolina]()

Reconstruction drawing showing known monuments of Aelia Capitolina

(the Eastern Cardo & Temple of Asclepius are missing) – Ritmeyer Archaeological Design

The 7th century Christian Chronicum Paschale lists several other buildings in Aelia Capitolina; two public baths, a theatre, a nymphaeum of four porticoes (perhaps the Pool of Siloam), a triple celled building (the Capitolium?), a monumental gate of twelve entrances (a circus?), and a quadrangular esplanade. However none of these buildings have been archaeologically located.

The Cardos

On the basis of Jerusalem’s depiction on the 6th century AD Madaba map (mosaic depicting the layout of Jerusalem, discovered in a Byzantine church in Madaba, Jordan), it is usually assumed that from the Damascus Gate in the north of the city (Porta Neapolitana) ran two wide colonnaded streets, the Western and Eastern cardos (Cardo Maximus & Lower Cardo). The Cardo Maximus is shown in the center of the mosaic with a pillared colonnade on both sides running south to the camp. Another smaller eastern street was connecting the north gate to the south part of the city, passing between the temple mount and the upper city and reaching the Dung Gate. It is indicated by a single line of columns crossing the top side of Jerusalem.

![Reproduction of the 6th century AD map of Aelia Capitolina (Jerusalem)]()

Reproduction of the 6th century AD map of Aelia Capitolina

Paved and lined with columns, the Cardo Maximus was the main road that ran through the Roman and Byzantine city and also served as the center for the local economy.

![]()

Artist’s reconstruction of life in a Western Cardo of Jerusalem during the Aelia Capitolina period

Major sections of this 1900-year-old street have been excavated and are reused in today’s Jewish Quarter in the Old City of Jerusalem. The entire roadway was originally 22 meter wide (40 feet) while the road itself was 5 meter wide (16 feet) with colonnaded and covered passageways on both sides to protect pedestrians from traffic and the heat of the sun. Shops lined the colonnades in its southwestern section.

![Reconstructed section of the Cardo Maximus of Aelia Capitolina © Carole Raddato]()

Reconstructed southern section of the Cardo Maximus of Aelia Capitolina

© Carole Raddato

![Reconstructed section of the Cardo Maximus of Aelia Capitolina © Carole Raddato]()

Reconstructed section of the Cardo Maximus of Aelia Capitolina

© Carole Raddato

The excavation of the Western Cardo by Professor Nahman Avigad of the Hebrew University began in 1975 and lasted two years. A 200 m long section of the cardo was exposed 4 meter below the present street level. Today visitors can get a good idea of how the cardo looked like just beyond the entrance to the Jewish Quarter where two sections of the main street have been reconstructed. While some of the column bases were found in situ, most of the architectural features were reused in later structures that lined the cardo.

![Reconstructed southern section of the Cardo Maximus of Aelia Capitolina © Carole Raddato]()

Reconstructed southern section of the Cardo Maximus of Aelia Capitolina with the wooden roof planks

© Carole Raddato

However the Hadrianic Western Cardo did not stretch this far south until centuries later. This portion dates to the time of Emperor Justinian. During the 6th century AD the city became an important Christian center with a rapidly growing population. The southern section was built to link the cardo to the two main churches of Byzantine Jerusalem, the Holy Sepulcher and the Nea Church.

![Reconstruction drawing of the Eastern Cardo of Colonia Aelia Capitolina]()

Artist’s reconstruction of life in a Eastern Cardo of Jerusalem during the Aelia Capitolina period

Recent archaeological excavations in the heart of Jerusalem’s Old City have exposed several sections of the Eastern Cardo. Beneath the level of the Western Wall Plaza, at a depth of 5–6 meters, archeologists discovered the remains of a wide paved and colonnaded street, complete with shops on each side (much like the Western Cardo). An Hadrianic date for the construction of the cardo was determined based on the finds discovered just beneath the paving stones. On the basis of these finds, archaeologists now suggest that the Roman city was planned and its main thoroughfares paved in the early years of Hadrian’s reign, about a decade before his visit to the East. (Source)

!["Cotell2" by Zivya - Own work. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons - http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cotell2.JPG#mediaviewer/File:Cotell2.JPG]()

Excavation site in the Western Wall plaza where the remains of the Eastern Cardo was discovered

“Cotell2″ by Zivya – Own work. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons -

The Northern Gate, Porta Neapolitana

Underneath the Damascus Gate (built in the 16th century AD under the rule of the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent), remains of a gate dating to the time of Hadrian have been discovered and excavated. This gate features on the Madaba Map, which shows an open square with a column inside the gate.

![Reproduction of the Madaba Map showing the Damascus Gate]()

Reproduction of the Madaba Map showing the Northern Gate of Aelia Capitolina, the broad plaza and the column supporting the statue of Hadrian

This impressive Hadrianic gateway, built with Herodian stones, consisted of a large arched passageway – situated beneath the opening of today’s Damascus Gate – flanked by two smaller, lower arches. It was protected on both sides by two guard towers. However, by the time the Madaba Map was made, the side passageways were blocked and only the central one was still in use. In front of the gate was a broad plaza, in the center of which stood a column supporting a statue of Hadrian at its top. Only the eastern entrance of the gate with its flanking tower has survived which can be seen below the modern raised walkway entering the Damascus Gate. The Roman gate of Aelia Capitolina has been restored and opened to the public; upon descending below the bridge leading to the Ottoman Damascus Gate, one can enter once again through this early gate into the city.

![The Northern Gate of Aelia Capitolina beneath the Damascus Gate, built in 135 AD, Jerusalem © Carole Raddato]()

The eastern arch of the Northern Gate of Aelia Capitolina beneath the Damascus Gate, built in 135 AD

© Carole Raddato

One stone, just above the lintel of the arch, bears a battered Latin inscription with the city’s name under Roman rule, Aelia Capitolina. The end of the inscription reads, “.. by the decree of the decurions of Aelia Capitolina.” The corridor beyond the surviving arch leads to the interior of the eastern gate tower. The tower has been preserved in its full height (12 meters) and only its ceiling is a later addition.

Inside the Hadrianic gate, a paved open area corresponding to the oval plaza we see on the Madaba Map is still preserved, from which the two main streets led down to two forums. A similar circular space is preserved at Gerasa (modern Jerash in Jordan), one of the Decapolis cities which, like Jerusalem, was rebuilt by Hadrian.

![Paved open area preserved under the Damascus Gate, Aelia Capitolina © Carole Raddato]()

Paved open area preserved under the Damascus Gate

© Carole Raddato

![Roman soldiers’ game carved into the pavement under the Damascus Gate, Aelia Capitolina © Carole Raddato]()

Roman soldiers’ game carved into the pavement under the Damascus Gate

© Carole Raddato

The original staircase that leads to the top of the tower is preserved to its original form and leads today to the Wall Walk.

![The Damascus Gate (built in the 16th century AD under the rule of the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent © Carole Raddato]()

The Damascus Gate built over the remains of the Hadrianic gate

© Carole Raddato

The Triumphal Arch

Built in the style of a triumphal arch, the so-called Ecce Homo Arch, located near to the eastern end of the Via Dolorosa, is the central span of what was originally a triple-arched gateway. It was similar in purpose to the Arch of Titus in Rome commemorating the AD 70 victory over the Jews.

![The Ecce Homo arch, a triple-arched gateway, built by Hadrian, as an entrance to the eastern Forum of Aelia Capitolina, Jerusalem © Carole Raddato]()

The Ecce Homo arch, a triple-arched gateway, built by Hadrian, as an entrance to the eastern Forum of Aelia Capitolina

© Carole Raddato

The central arch was flanked by two smaller arches, one of which can still be seen inside the Ecce Homo Church. The second small arch was incorporated in the 16th century into a Uzbek dervishes monastery on the other side of the Via Dolorosa street, but this was later demolished, taking the arch with it.

![The so-called Ecce Homo arch, a triple-arched gateway, built by Hadrian, as an entrance to the eastern Forum of Aelia Capitolina, Ecce Homo Church, Jerusalem © Carole Raddato]()

The so-called Ecce Homo arch, a triple-arched gateway, built by Hadrian as the entrance to the eastern Forum of Aelia Capitolina

© Carole Raddato

Traditionally, the arch was said to have been part of the gate of Herod’s Antonia Fortress, which itself was alleged to be the location of Jesus’ trial by Pontius Pilate. However, since the late 1970’s, archaeologists have established that the arch was a triple-arched gateway built by Hadrian. It served as the eastern entrance of the Forum of Aelia Capitolina located to the west of the main north-south cardo.

![The Ecce Homo arch, a triple-arched gateway, built by Hadrian, as an entrance to the eastern Forum of Aelia Capitolina © Carole Raddato]()

The Ecce Homo arch, a triple-arched gateway, built by Hadrian, as an entrance to the eastern Forum of Aelia Capitolina

© Carole Raddato

The Forum

Hadrian established two forums in Aelia Capitolina, one north of the Temple Mount and the other on the western side of the city. Both were large, open, paved spaces surrounded by temples and public buildings. Only the northern forum has been located with certainty. At the start of the 20th century, the French religious-archaeologist Father Louis-Hugues Vincent discovered a large expanse of ancient pavement immediately beneath the Convent of the Sisters of Zion. He declared that it was the “lithostrotos” of John’s gospel (the location of Pontius Pilate’s judgment of Jesus). Archaeology has proven conclusively that the pavement was associated to the arch and was part of the Hadrianic forum.

![The paving of Hadrian's forum, thought to have been the "lithostrotos" of of John's gospel, Aelia Capitolina © Carole Raddato]()

The flagstone pavement of Hadrian’s forum, thought to have been the “lithostrotos” of of John’s gospel

© Carole Raddato

The site of the forum had previously been a large open-air pool of water called the Struthion Pool. It was built in 1st century BC next to the Antonia Fortress, a military barracks built around BC 19 by Herod the Great. The Herodian pool was laying in the path of the northern decumanus, so Hadrian added arch vaulting to enable the pavement to be placed over it. Beneath the paving is a large cuboid cistern which gathered the rainwater from guttering on the Forum buildings.

![The paving of Hadrian's forum, thought to have been the "lithostrotos" of of John's gospel, Aelia Capitolina © Carole Raddato]()

The paving of Hadrian’s forum, thought to have been the “lithostrotos” of of John’s gospel

© Carole Raddato

The Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus on Temple Mount

At the excavation site in the Western Wall plaza, archeologists also uncovered two small streets that ran perpendicularly and led east from the cardo toward the Western Wall of the Temple Mount. This discovery may indicate that, during the early 2nd century AD, the Temple Mount area had something important standing in the place where the destroyed Second Temple once stood. Some scholars have proposed that there was once a temple – to Jupiter Capitolinus or some other Roman deity or combination of deities – that was built at the site of the Second Temple after Jerusalem had been transformed into a pagan city. In addition to Dio Cassius, other written sources implied that such was the case, but little archaeological evidence had ever been recovered to confirm or support this claim until the discoveries of these two small streets.

In AD 333, the “Bordeaux Pilgrim” mentioned that he saw two statues of Hadrian near the temple mount and that there was a building over the place of the Jewish Temple.

“There are two statues of Hadrian, and not far from the statues there is a perforated stone, to which the Jews come every year and anoint it, bewail themselves with groans, rend their garments, and so depart.”

– The Bordeaux Pilgrim, Itinerary 7a

However it has been thought that the pilgrim may have mistaken the statue of Antoninus Pius with that of Hadrian. This can be revealed by an inscription which today appears upside-down on the wall above the Double Gate located on the southern Temple Mount Wall. This inscription, reused by later Islamic builders, could have been engraved upon the pedestal of Antoninus Pius’ equestrian statue.

![Upside down inscription is from the Roman statue of Emperor Antoninus Pius that the Bordeaux Pilgrim recorded seeing when he was on the Temple Mount in 333 AD, Aelia Capitolina © Carole Raddato]()

Upside down inscription is from the Roman statue of Emperor Antoninus Pius that the Bordeaux Pilgrim recorded seeing when he was on the Temple Mount in 333 AD

© Carole Raddato

Shown rightside-up, the inscription reads:

![The Antoninus Pius inscripion shown rightside-up © Carole Raddato]()

The Antoninus Pius inscripion shown rightside-up

© Carole Raddato

“To Titus Aelius Hadrianus

Antoninus Augustus Pius

The father of the fatherland, pontifex, augur

Decreed by the Decurions”

![Double Gate located on the southern Temple Mount Wall © Carole Raddato]()

Double Gate located on the southern Temple Mount Wall

© Carole Raddato

In AD 398, Saint Jerome‘s commentary on Matthew mentioned that an equestrian statue of the Emperor Hadrian was still standing directly over the site of the Holy of the Holies, then consecrated to Jupiter Capitolinus.

“So when you see standing in the holy place the abomination that causes desolation: or to the statue of the mounted Hadrian, which stands to this very day on the site of the Holy of Holies.“

– Jerome, Commentaries on Isaiah 2.8: Matthew 24.15

Therefore it is reasonable to assume that there was an equestrian statue on the Temple Mount. These statues were probably destroyed by the Byzantine Christians after AD 333, the Jews in AD 614 or the Muslims in AD 638. This reused block (spolia) is the only part of the two statues found so far.

If a temple of Jupiter Capitolinus existed on Temple Mount, it is probable that the new sacred precinct had similar enclosures to that of the Temple of Jupiter that Hadrian built at Heliopolis (Baalbek). It is a theory put forth by the Tel Aviv architect Tuvia Sagiv, who has noted the striking similarity in both design and scale between the temple complex of Jupiter in Baalbek and the present arrangement of Islamic buildings on Temple Mount.

![Temple of Jupiter, Baalbek]() The standard pattern for such temples, as seen in the image above, was an entry through a propylon and an octagonal portico, a plaza with an altar, and the temple proper. Sagiv argues that when the architecture of the temple complex of Jupiter in Baalbek is overlaid on the Temple Mount, it matches the Al Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock exactly (see the overlaid image here).

The standard pattern for such temples, as seen in the image above, was an entry through a propylon and an octagonal portico, a plaza with an altar, and the temple proper. Sagiv argues that when the architecture of the temple complex of Jupiter in Baalbek is overlaid on the Temple Mount, it matches the Al Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock exactly (see the overlaid image here).

If Tuvia Sagiv is correct, then the Dome of the Rock is not the actual site of the Jewish temple. He suggests the Dome of the Rock was built upon the remains of the temple built by Hadrian (read more here).

The Temple of Asclepius & Serapis

In digs conducted in 1964 near the Church of Saint Anne, archaeologists discovered the remains of Hadrian’s Temple of Asclepius – the god of healing – and Serapis. Between 150 BC and 70 AD, a popular healing center developed on the site of the Pool of Bethesda, the water reservoirs that supplied water to the temple mount in the 3rd century AD. A water cistern, baths and grottoes were arranged for medicinal or religious purposes. In the mid 1st century AD, Herod Agrippa built a popular healing center, the asclepeion.

![Excavations at the Pool of Bethesda showing the ruins of the Temple of Serapis with a column from an early Christian church, Aelia Capitolina © Carole Raddato]()

Excavations at the Pool of Bethesda showing the ruins of the Temple of Serapis with a column from an early Christian church (next to St Anne’s Church)

© Carole Raddato

When Hadrian rebuilt Jerusalem as Aelia Capitolina, he expanded the asclepeion into a large temple to Asclepius and Serapis. Several votive offerings were discovered at the site of the temple including a small edicule with snake – the symbol of Asclepius – and wheat ears, a statuette representing a woman getting ready for bathing as well as a Roman coin minted in Aelia Capitolina figuring the god Serapis.

![Antoninus Pius mint form Aelia Capitolina, 138-161 AD CAP COAE Draped bust of Serapis right, wearing modius]()

Antoninus Pius. AD 138-161. Laureate head of Antoninus Pius right / Draped bust of Serapis right, wearing modius

![Marcus Aurelius, with Commodus. AD 161-180. Confronted busts of Marcus and Commodus, each laureate, draped, and cuirassed / Draped bust of Serapis right, wearing modius.]()

Marcus Aurelius, with Commodus. AD 161-180. Confronted busts of Marcus and Commodus, each laureate, draped, and cuirassed / Draped bust of Serapis right, wearing modius.

In the Byzantine era, the asclepeion was converted into a church.

![Ruins of the Temple of Serapis with a column from an early Christian church © Carole Raddato]()

Ruins of the Temple of Serapis with a column from an early Christian church (next to St Anne Church)

© Carole Raddato

The Temple of Aphrodite

At the junction of the Cardo Maximus with the Decumanus of Aelia, Hadrian’s architects laid out a vast forum (which is now the location of the Muristan). A sacred precinct was built adjacent to this forum in the area now occupied by the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the purported tomb of Jesus and Calvary itself. According to Eusebius, Hadrian built a temple dedicated to the Roman goddess Venus in order to bury the cave in which Jesus had been buried.

![The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the place where © Jorge Láscar]()

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre built over the Hadrianic Temple of Aphrodite

© Jorge Láscar

The sources give conflicting reports but it seems the honoured god of the pagan sanctuary was Hadrian’s own family deity Aphrodite, a goddess also sacred to the occupying 10th legion: the emblem on its Vexillum standard was the Taurus, the zodiacal sign for April, the time of year when the legend was founded and auspicious to Aphrodite. The Hadrianic temple was completely destroyed by the Emperor Constantine the Great 180 years later. He ordered that the temple be replaced by a church.

The Hadrianic temple was surrounded by a temenos (a sanctified area, marked by a protective wall) with a main entrance on the Cardo Maximus. In the 1970s, in the Chapel of Saint Vartan deep beneath the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, archaeologists discovered part of the original ground level and the protective walls of Hadrian’s temple enclosure (see image here). One of these walls has a stone etched with a merchant ship and an inscription “DOMINE IVIMVS” which translates “Lord, we shall go” (see image here). It is estimated that this stone dates from before the completion of the Byzantine church. It seems to indicate that the site of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was regarded as the authentic Golgotha even when a pagan temple stood there.

Coins minted in Aelia Capitolina

City coins were issued from the time of Hadrian to that of Valerianus (260) but are especially plentiful from the times of Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius, Eleagabalus, and Trajan Decius. The 206 coin types depict the many gods worshiped in Aelia Capitolina: Serapis, Tyche, Dionysus, the Dioscuri, Roma, Ares, Nemesis are all to be found in addition to the Capitoline triad.

![Antoninus Pius. AD 138-161. Laureate, draped, and cuirassed bust right / The Dioscuri standing facing, each holding spear.]()

Antoninus Pius. AD 138-161. Laureate, draped, and cuirassed bust right / The Dioscuri standing facing, each holding spear.

Aelia was a quiet provincial city but great events such the imperial visit of Septimius Severus in 201 also took place. It was commemorated by an inscription discovered near the Western Wall. On this occasion the colony received the honorary title “Commodiana Pia Felix”, appearing for the first time on the coins of Geta.

![]()

Elagabalus coin bearing the new name of the city Aelia Capitolina Commodiana Pia Felix COL AEL CAP COM P F on the reverse with bust of Serapis wearing modius

Epigraphic evidence

As recently as two weeks ago, on Wednesday 22nd October (the day I arrived in Jerusalem), a rare find of historical significance was unveiled and displayed to the public by the Israel Antiquities Authority: large slab of limestone engraved with an official Latin inscription dedicated to Hadrian.

![Photo of the Latin inscription set against the Rockefeller Museum, seat of the Israel Antiquities Authority in Jerusalem © Carole Raddato]()

Photo of the Latin inscription set against the Rockefeller Museum, seat of the Israel Antiquities Authority in Jerusalem

© Carole Raddato

The fragmented stone, roughly a meter wide, with Latin text inscribed in six lines, might have been part of a monumental arch dedicated Hadrian in 130 in honor of his imperial visit. Researchers believe this is among the most important Latin inscriptions ever discovered in Jerusalem and may shed light on the timeline of Jerusalem’s reconstruction.

![Latin inscription dedicated to Hadrian found in Jerusalem, it was incorporated in secondary use around the opening of a deep cistern © Carole Raddato]()

Latin inscription dedicated to Hadrian found in Jerusalem, it was incorporated in secondary use around the opening of a deep cistern

© Carole Raddato

Their analysis revealed that this inscription is the right half of an inscription discovered nearby in the late 19th century by the French archaeologist Charles Clermont-Ganneau. The two slabs are currently on display in the courtyard of Studium Biblicum Franciscanum Museum.

![Two fragments of an imperial inscription in Latin from Aelia Capitolina dedicated to Hadrian, on display in the courtyard of Studium Biblicum Franciscanum Museum, Jerusalem © Carole Raddato]()

Two fragments of the imperial inscription dedicated to Hadrian, on display in the courtyard of Studium Biblicum Franciscanum Museum, Jerusalem

© Carole Raddato

Putting the slabs together, the complete inscription reads:

”To the Imperator Caesar Traianus Hadrianus Augustus, son of the deified Traianus Parthicus, grandson of the deified Nerva, high priest, invested with the tribunician power for the 14th time, consul for the third time, father of the country [dedicated by] the 10th legion Fretensis (second hand) Antoniniana”

The new part of the inscription provides confirmation that the Tenth Legion was in Jerusalem during the period between the two revolts, the destruction of the Second Temple in AD 70 and the Bar Kokhba revolt.

![Tile fragment with a stamp of the Tenth Legion, "LG X F", and its symbol, a wild boar and a battleship, found in Jerusalem, 1st-2nd century AD, Israel Museum © Carole Raddato]()

Tile fragment with a stamp of the Tenth Legion, “LG X F”, and its symbol, a wild boar and a battleship, found in Jerusalem, 1st-2nd century AD, Israel Museum

© Carole Raddato

The inscription may also help researchers to understand the historical factors that led to the Bar Kokhba revolt. Did the construction of Aelia Capitolina and the building of a pagan temple on the site of the Jewish Temple Mount lead to the revolt? Or did these two events were putative measures Hadrian took against Jerusalem in the aftermath of the revolt?

During the reign of Constantine the Great, in the fourth century AD, Jerusalem became an important Christian city. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was built on the site of the Temple of Aphrodite and the Basilica of Holy Zion at the south of the Western Hill.

Two and a half centuries later, Justinian built the massive Nea Church and extended the Roman Cardo further south. The Temple Mount was left in ruins.

![Reconstruction drawing of Aelia Capitolina - Ritmeyer Archaeological Design]()

Reconstruction drawing of Byzantine Aelia Capitolina – Ritmeyer Archaeological Design

Sources:

- The Archaeology of the Holy Land: From the Destruction of Solomon’s Temple by Jodi Magness (Cambridge University Press 2012)

- Keys to Jerusalem: Collected Essays By Jerome Murphy-O’Connor (Oxford Univ Pr 2012)

- The Foundation of Aelia Capitolina in Light of New Excavations along the Eastern Cardo by Shlomit Wekshler-Bdolah, Israel Antiquities Authority (2014 Israel Exploration Society)

-

The location of the Temple on the Temple Mount based on the Aqueduct and rock levels at Mount Moriah in Jerusalem by Tuvia Sagiv (2008) (

Read online)

-

A Rare 2,000 Year Old Commemorative Inscription Dedicated to the Emperor Hadrian was Uncovered in Jerusalem (october 2014) published by the

Israel Antiquities Authority

-

-

Archaeological researches in Palestine during the years 1873-1874 by Charles Clermont-Ganneau Vol. 1 (Published 1896 by Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund in London) (

Read online)

![Here I am in front of the Latin inscription dedicated to Hadrian reveiled in Jerusalem on Wednesday 20th October 2014 © Carole Raddato]()

Here I am in front of the Latin inscription dedicated to Hadrian reveiled in Jerusalem on Wednesday 22th October 2014

© Carole Raddato

Filed under:

Archaeology Travel,

Epigraphy,

Hadrian,

Israel,

Judaea,

Photography,

Roman Army,

SPQR Tagged:

Aelia Capitolina,

Carole Raddato,

Colonia Aelia Capitolina,

Emperor Hadrian,

Jerusalem ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()